When I first asked myself, “where did yoga originate?” I found out how deep its history really is.

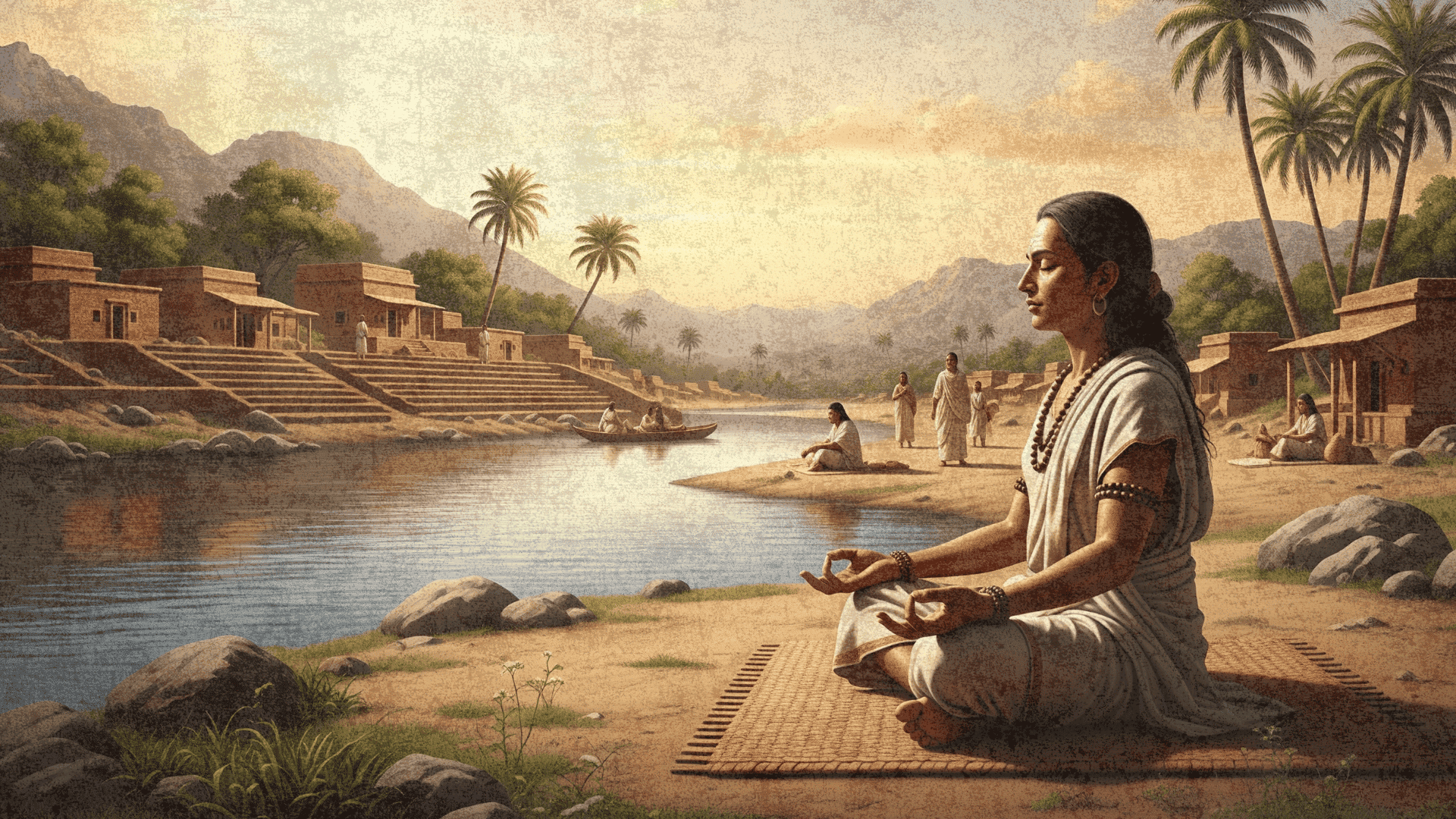

I learned that yoga began in ancient northern India, especially in the Indus-Sarasvati region, thousands of years ago. The earliest sacred writings, like the Vedas and Upanishads, showed me that yoga was never just about physical poses.

It was meant to unite body, mind, and spirit, offering a path toward balance and focus.

If you’ve ever wondered the same, knowing these origins can give you a deeper respect for yoga’s roots. Understanding its history helps you see it as more than an exercise. It’s a practice with spiritual meaning that has traveled across cultures and shaped wellness worldwide.

Where Did Yoga Originate?

Yoga’s origins trace back over 5,000 years to ancient northern India, particularly the Indus Valley Civilization. Archaeological finds like seals showing figures in meditative postures give the earliest hints.

The Vedic period (roughly 1500–500 BCE) laid a spiritual foundation with texts called the Vedas, which included hymns and rituals that shaped early yogic ideas.

Later, the Upanishads (around 700–500 BCE) introduced philosophical concepts such as meditation and the inner self. Over centuries, yoga evolved into various traditions, culminating in classical teachings like Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras around 200 BCE.

The physical postural yoga familiar today mainly developed in the 19th and 20th centuries, blending ancient wisdom with modern adaptations.

Archaeological Clues: The Indus-Sarasvati (Indus Valley) Evidence

The earliest signs potentially linked to yoga come from archaeological discoveries made in the Indus-Sarasvati or Indus Valley Civilization.

These relics provide intriguing glimpses into ancient practices that may have influenced later yogic traditions, though they stop short of offering direct proof.

Stone seals from around 3300–1300 BCE exhibit figures in cross-legged, meditative postures suggestive of ascetic or contemplative traditions. These depictions are among the oldest physical artifacts that hint at meditation-like practices.

Yet, scholars caution that they are symbolic images rather than explicit yoga manuals, meaning their connection to classical yoga is interpretive.

Museum summaries and Google Arts & Culture highlight these artifacts as important cultural markers but emphasize the speculative nature of such links to yoga.

How Do Archaeologists and Historians Interpret Those Finds?

Experts generally agree that these archaeological finds suggest possible precursors to yoga, representing early ritualistic or meditative behavior in ancient India.

However, they do not constitute conclusive evidence of organized yogic systems. These artifacts are best understood as part of a broader cultural context that set the stage for the textual and philosophical developments that followed.

This careful interpretation balances enthusiasm for learning with academic caution.

Earliest Textual Evidence: Vedas and Early Upanishads

Written records provide clearer, though still evolving, evidence of yoga’s conceptual foundations, especially within the Vedic scriptures and early Upanishads.

The Rigveda, dating roughly to 1500 BCE, contains the Sanskrit root yuj, meaning “to yoke” or “to unite,” which is pivotal in yoga’s philosophical framework. These texts describe rituals and ascetic practices aiming at spiritual concentration and self-mastery, laying the groundwork for later yogic thought.

While the Rigveda doesn’t detail yoga as a system, it plants conceptual seeds pointing to union between body, mind, and cosmos.

Upanishads: First Mature Philosophical Concepts of Yoga

The Katha and Shvetashvatara Upanishads, composed between 700 and 500 BCE, articulate more developed ideas about yoga.

They describe yoga as a disciplined practice of controlling the mind and senses, leading to spiritual liberation (moksha).

These texts shift focus from external rituals toward inner awareness and self-realization, representing the first mature philosophical exposition of yoga that influenced classical texts such as Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

Classical Codification: Patanjali and the Yoga Sūtras (c. 2nd century BCE–5th century CE)

Patanjali’s Yoga Sūtras synthesized Samkhya philosophy and Buddhist practices into “classical yoga,” though the text fell into obscurity for 700 years before colonial revival.

The eight-limbed (ashtanga) system has 31 of 195 aphorisms but became foundational to later frameworks.

| Limb | Sanskrit | Function | Key Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Yama | Ethical restraints | Ahimsa, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, Aparigraha |

| 2nd | Niyama | Personal observances | Saucha, Santosha, Tapas, Svadhyaya, Ishvara pranidhana |

| 3rd | Asana | Stable posture | “Steady, comfortable” seat; no specific poses described |

| 4th | Pranayama | Breath regulation | Control of inhalation, exhalation, and retention |

| 5th | Pratyahara | Sensory withdrawal | Drawing awareness from external to internal |

| 6th | Dharana | Concentration | One-pointed focus on a single object/concept |

| 7th | Dhyana | Meditation | Sustained awareness without effort |

| 8th | Samadhi | Absorption | Union with the object; realization of kaivalya |

Influence: Medieval yoga was dominated by the Bhagavad Gita and Tantric traditions rather than Patanjali. Modern elevation occurred only in the past 40 years through Vivekananda and colonial scholarship.

Medieval Developments: Hatha, Tantric Streams, and the Rise of Bodily Practices

In the medieval period, yoga shifted focus from purely spiritual to more physical and energy-based methods. This phase solidified key techniques that shape modern yoga’s foundation today.

- The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (15th century) systematized physical postures (asanas), breathwork (pranayama), and cleansing rituals.

- Tantric yoga introduced energetic anatomy concepts like chakras, nadis, and awakening kundalini energy.

- Asana practice evolved beyond meditation seats to include varied, dynamic poses for bodily discipline.

- Breath regulation (pranayama) became central to controlling life force and aiding meditation.

These developments moved yoga into an embodied science, integrating physical, energetic, and spiritual paths essential to contemporary practice Oxford Bibliographies.

Yoga’s Rise in Modern Times and Its Worldwide Expansion

Yoga entered a new phase starting in the late 19th century, adapting to changing cultural and political landscapes in India and beyond. This period gave rise to dynamic physical yoga forms and expanded yoga’s reach worldwide.

Modern postural yoga emerged largely through Indian teachers like Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who integrated traditional yogic teachings with Western physical culture such as gymnastics and bodybuilding.

Unlike classical yoga, which emphasized meditation and spiritual liberation, modern postural yoga focused more on physical postures (asanas) and breath control (pranayama) for health and vitality.

This shift aligned with Indian nationalist goals to promote a strong, healthy body as a symbol of cultural pride during colonial rule.

Global Spread and Commercialization

Yoga’s global popularity soared throughout the 20th century as it spread to North America, Europe, and beyond. It evolved into multiple forms, including fitness, wellness, and spiritual practices, adapting to diverse audiences.

Yoga’s commercialization included book publishing, teacher training programs, studios, and wellness products, making it a multi-billion-dollar global industry.

While the spiritual roots remain, the modern yoga market reflects a broad spectrum of motivations and ways of practicing yoga.

Common Myths and Contested Claims

Yoga’s long history has led to many myths and misunderstandings, especially about where it began and what it truly represents.

Some people believe yoga started outside of India, but history shows it originated in ancient India over 5,000 years ago, with early references in the Rig Veda and evidence from the Indus-Sarasvati civilization.

Another common myth is that yoga is only about exercise. While modern yoga often highlights physical poses, classical yoga is rooted in uniting body, mind, and spirit, with the ultimate goal of spiritual growth as outlined in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

Some also assume yoga belongs to a single religion. In truth, yoga has influenced Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and beyond, and today it is practiced in both spiritual and secular ways. Over time, yoga has continually evolved, adapting to cultures and lifestyles worldwide.

Why the Question “Where Did Yoga Originate” Matters Today?

Knowing that yoga originated in ancient India isn’t just a historical detail; it shapes how the practice is understood and shared today. As yoga spread worldwide, some studios began offering only the physical side without acknowledging its Indian roots or philosophy.

This separation has led to criticism from Indian scholars who see it as a loss of authenticity and cultural context. In response, many teachers and academics from India now publish work, hold workshops, and speak at global events to explain yoga’s lineage and meaning.

They call for using Sanskrit names, crediting traditional texts, and teaching ethical foundations alongside postures. These discussions show why origin matters: remembering where yoga began helps prevent its reduction to a fitness trend and encourages respectful, informed practice.

By connecting the past to the present, you see how yoga’s birthplace continues to guide its global future.

Conclusion

Looking back at yoga’s origins, I feel a deeper connection to its history and meaning that goes beyond the poses.

It’s amazing to see how yoga has traveled through thousands of years, influenced by culture, philosophy, and modern innovation. This understanding makes every practice feel more alive.

I’m curious to learn what part of yoga’s story resonates with you.

Please share your thoughts or questions, and check out other blogs on the website! No matter your experience level, I hope this glimpse into yoga’s roots inspires a more mindful and respectful practice for you.